How did paper peed on by a dog become a work of art? Who decided that? Do we and must we accept it? The Tale of Three Painters concerns us with these questions. Its author, the brilliant ironist Josef Váchal, fortunately suggested a solution: Humor is the best defense against fraud in art.

The Tale of Three Painters

Although Josef Váchal is now generally respected as a visual artist, his no less original literary work is yet to be appreciated. In addition to the partially hermetic content of his writings, this is caused by a rather idiosyncratic style based on a parody of various literary genres, from the popular to the scientific. Váchal's irony and satire are not self-serving, but often convey important ideas and critical observations. The author's book New tolerance calendar for the year 1923 is a magnificent mystification, ingeniously parodying not only the genre of the popular reading calendar, but also the contemporary social conditions and personalities of cultural life (F. Bílek, J. Deml, A. Procházka). Hear the Tale of the Three Painters from this persiflage.

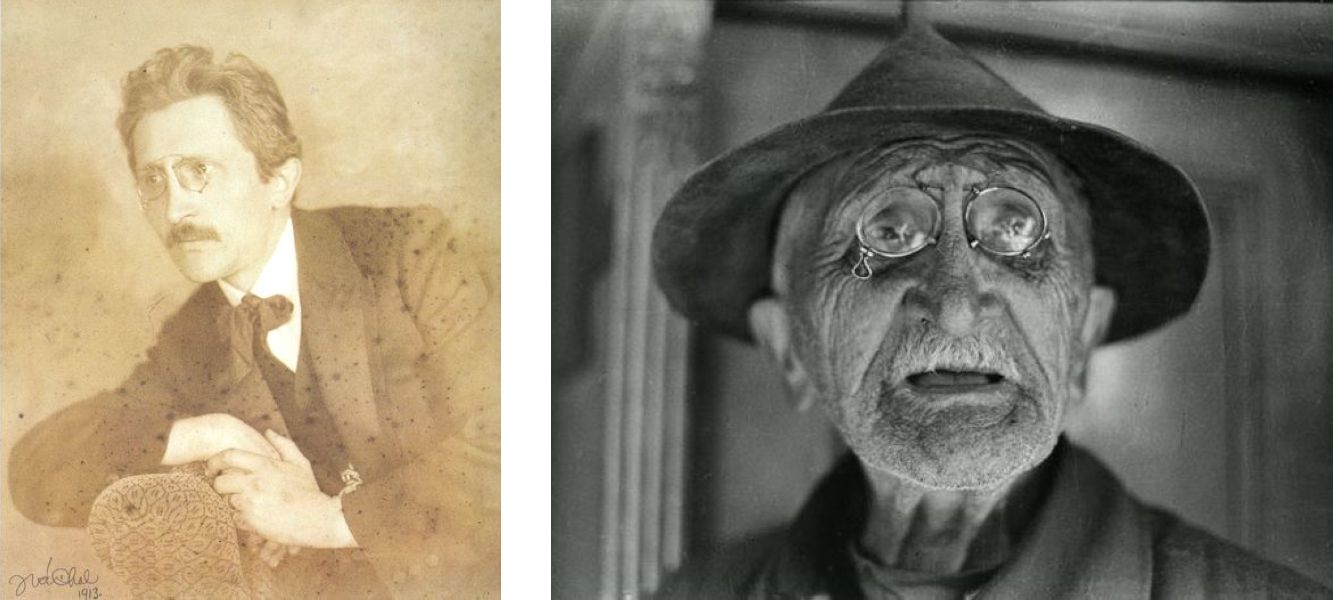

Fig. 1. Josef Váchal, 1913

Fig. 2. Josef Váchal, 1967, photo by Dagmar Hochová

There lived three painter brothers. When the father who fed them died, the oldest brother relying on his faith went out into the world to provide everyone with a living. Later, so did the middle brother, who depended more on his talent and diligence. When it was the youngest's turn, he decided to rely on his cunning instead of faith and talent. He took the pile of papers that his old dog who "not able to hold his urine, sprinkled" and headed to the Ministry of Education and Enlightenment to the all-powerful official V. V. Stychov. He presented himself as a pioneer of the new painting direction "Ursism", coming from France. The submitted work so captivated the official authority that it earned the shamelessly brash but courageous young man a state prize, artistic fame and a lifetime annuity in the form of public contracts.

Analysis of the Tale of Three Painters

If the fabricated story, with its shocking probability, reminds you of today's reality of the official Czech art scene, or if you even think that a very similar story has happened more than once in our present day and can be repeated at any time, then may I remind you that the Tale of Three Painters was written by Josef Váchal in 1922. His satire is actually directed against the cultural conditions of the First Czechoslovak Republic, generally against the uncritical and superficial adoption of modern trends in painting and especially against the one-sided, politically biased cult of French Cubism. The main target of sarcasm is the art critic V. V. Štech, who relies on the influence and authority of his office and who embodies these contemporary tendencies.

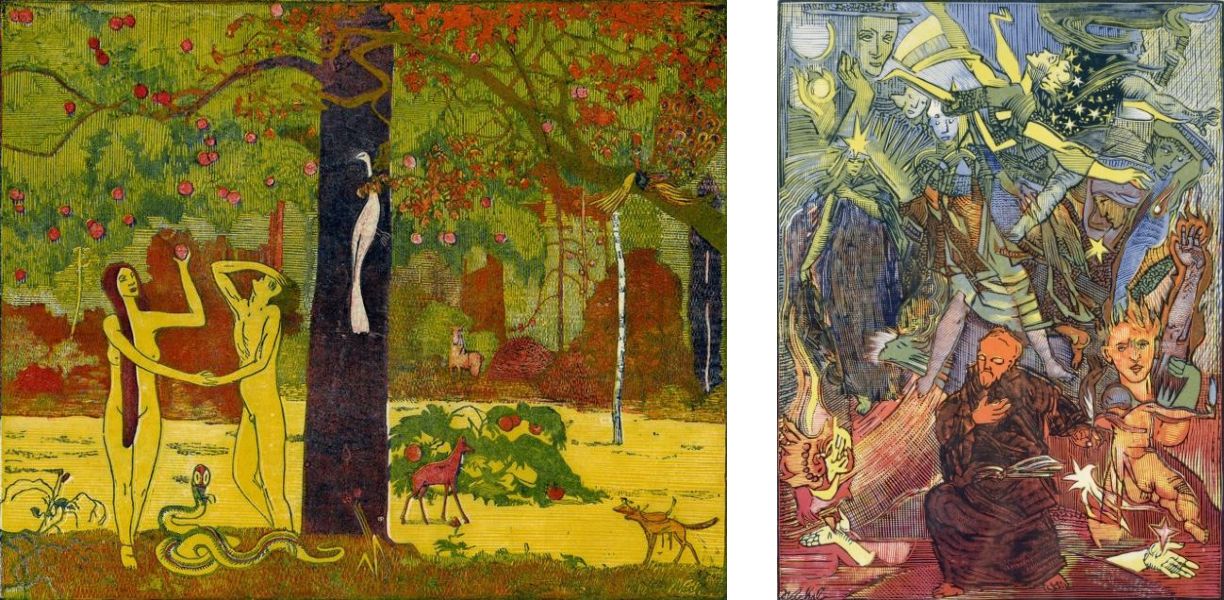

Fig. 3. Paradise, 1912, color woodcut

Fig. 4. Carol of Hearts, 1943, from a cycle of colored woodcuts based on the motifs of Otokar Březina’s poetry

Josef Váchal never encountered real manifestations of conceptualism during his lifetime. It is only a manifestation of his genius that he was able to so clairvoyantly predict the essence of Conceptualism more than four decades before its onset. Váchal expressed his theoretical views on art not only in the form of literary parody (in addition to the Tolerance Calendar, e.g. in the book Orbis pictus), but also in seriously intended reflections (the Recipe book of Color Woodcut and the On Art lecture). Both his ironic and serious criticism were mainly directed at two targets: the dishonesty of artists, consisting of deceptive self-presentation in the absence of talent, professional skills and work ethic; and the incompetence of critics, arising from a lack of erudition, ideological bias, protectionism and corruption.

Nevertheless, the fictional story of the youngest brother is worth a deeper reflection even today - especially today. The dog's "art" shows at least five features that I dare to call the characteristic features of conceptualism: (1) it was created from a different than aesthetic intention (the spontaneous leakage of dog urine), (2) it has a negligible, for some rather negative aesthetic value, (3) ) its creation did not require artistic talent and technical virtuosity, (4) it did not require a significant investment of time and work effort, (5) the interpretation of the work is purely voluntaristic, i.e. the declared content of the work is not at all related to its material essence and form. To this we can add a special feature, known in theory as appropriation: the author (painter) appropriates a work created in reality by someone else (dog).

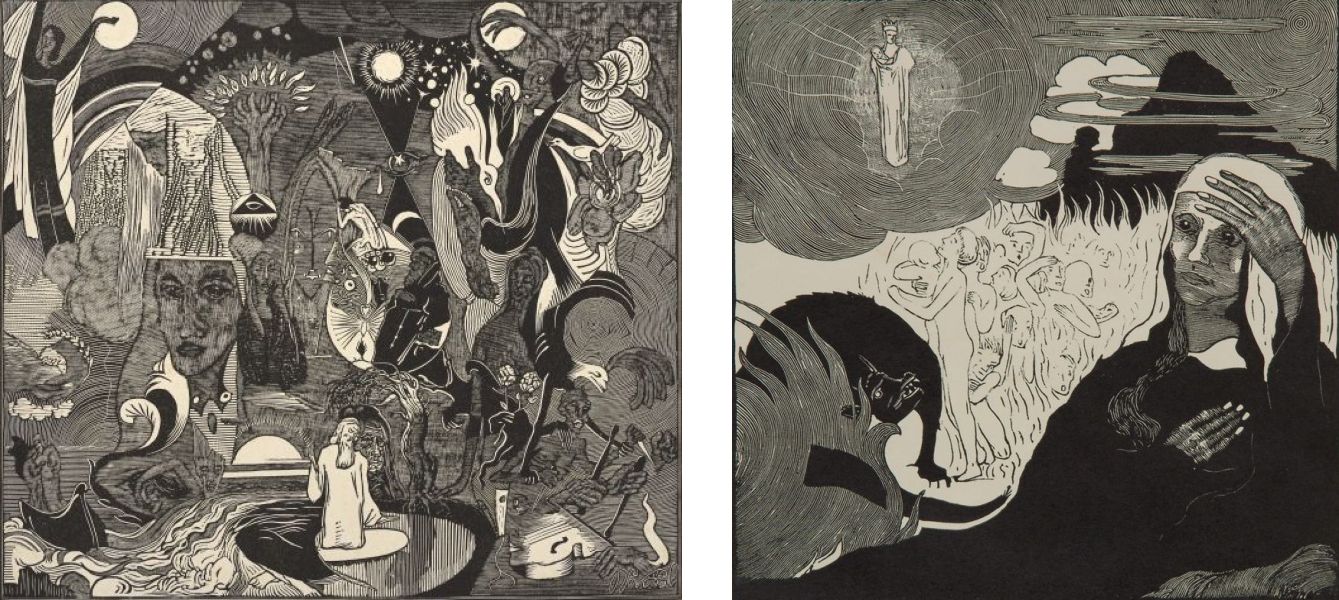

Fig. 5. Fragments for the work of Otokar Březina, 1915, monochrome woodcut

Fig. 6. Kateřina Anna Emmerichová, 1913, monochrome woodcut from the series Mystics and Visionaries

What is and what is not art

From the philosophical discourse on the nature of art in the 20th century, an aesthetic theory emerged, which defines a work of art as an artifact capable of evoking an aesthetic experience in the viewer. Alternatively, a work of art refers to an object created with the intention of fulfilling a primarily aesthetic function. Other meanings or functions, if they are contained in it, are not essential for granting the status of a work of art. Appreciating the quality of a work of art is no longer a task of definition, but of an accepted aesthetic norm. However, the aesthetic definition implies that an object created primarily with a non-aesthetic purpose is not a work of art and thus draws a clear cut between what is and what is not and cannot be a work of art.

In opposition to the aesthetic theory of art is the institutional theory, based on the ideas of Arthur Danto. According to this theory, granting the status of a work of art is a purely procedural act that is in the exclusive competence of the "art world", a virtual institution composed of influential theorists, gallerists and recognized artistic celebrities. The status of a work of art is consensually granted by this privileged body, without being subject to any rationally defined criteria and being objectively reviewable. Institutional theory is an expression of pure resignation to critical reason and ethical principles, but – and this must be admitted – it best reflects contemporary practice in the sphere of official art, where the dominant current is conceptualism with all its excesses and perversions.

Institutionalism is the fruit of logically defective thinking and value relativism. In addition to irrationality and amorality, one can also argue by pointing to its numerous historical failures in practice. I am referring to the inability to recognize the value of the artistic creation of solitary artists, creating outside the mainstream (such as Josef Váchal) and entire periods when the "art world" servilely subordinated its verdicts to the ruling ideology (the Nazi Third Reich and the communist regime).

Fig. 7. Self-portrait, 1921, color woodcut

Fig. 8. Dead Forest, 1931, color woodcut from the art book Šumava, Dying and Romantic

A triple defense against conceptualism

There are at least three ways to effectively defend against conceptualism. The first is to critically point out the deceptive and parasitic nature of this phenomenon, whose survival (unlike art!) is completely dependent on an institutional framework that is so susceptible to authoritarian arbitrariness and ideological influence. This is primarily a path for the theoretist. The second option that can be recommended to artists – as well as art lovers – is to ignore conceptualism altogether. An artist worthy of the name does not create according to the "progressive" trends of the time, but out of inner necessity, without craving for media fame and official recognition. American critic Harold Rosenberg argued that the best way to deal with kitsch is to ignore it and instead completely immerse self in art. I am convinced that this position can also be applied without modification to the defense against conceptualism, which is, after all, nothing more than intellectual kitsch.

There is still a third option open to everyone - every art lover as well as artist or theorist. The path of irony and humor bequeathed to us by Josef Váchal is a universal, powerful and timeless guide to defense against all frauds in art. The story about the three painters is not just a mockery of an arrogant fool, but like any good fairy tale it also contains a moral appeal. Master Váchal calls us not to be afraid to check the authority of revealed "truth" and to use critical reason in distinguishing art from non-art. Dog-pissed paper can easily be transformed into a conceptual "work" if properly appropriated, but it will never become a work of art, even if all three of the highest artistic authorities in the country announce it in unison - namely the National Gallery in Prague, the Academy of Fine Arts and the Jindřich Chalupecký Society...

Author: Jiří Bernard Krtička